Apparently so are members of Congress, who have failed to press the SEC to hold credit agencies accountable, as law requires, for the ratings they issue on securities backed by mortgages or other assets.

The law, part of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 that Congress passed in response to the crisis, was intended to fix a main cause of the meltdown: high but highly inaccurate credit ratings that firms, particularly S&P and Moody's, gave to the likes of investment bank Lehman Brothers before it failed, insurance giant AIG before it nearly failed and billions of dollars of subprime mortgage securities that proved worthless.

"I'm disappointed," says Barney Frank, the now retired congressmen from Massachusetts who, as chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, helped craft the act that bears his name.

So are investors, who say the SEC's inaction leaves the economy vulnerable. They worry an ongoing lack of accountability permits credit agencies to return to bad habits.

"(A) higher standard of accountability ... would make rating agencies more diligent about the ratings process and, ultimately, more accountable for sloppy performance," says Ann Yerger, head of the Council of Institutional Investors, a shareholder advocacy group representing pension funds, employee benefit funds, endowments and foundations with combined assets of more than $3 trillion.

Dennis M. Kelleher, CEO of Better Markets, a nonpartisan, nonprofit group pushing to make financial markets fairer and more transparent, agrees: "Credit rating agencies are critical and must be held liable for their failures. The SEC has failed the American people."

S&P, Moody's and smaller rival Fitch for decades have avoided legal liability by suc! cessfully arguing in court case after court case that credit ratings are merely opinions and therefore protected by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Dodd-Frank changes that. It requires the SEC hold credit rating agencies to the same standard of "expert liability" that auditors and lawyers face when they give opinions in financial filings with the agency.

The SEC issued a rule in 2010 doing just that. The credit agencies response? They went on strike, threatening to withhold ratings. That would have disrupted credit markets, which rely on the agencies' assessment of how creditworthy securities and the companies that issue them are. Specifically, it would have frozen the asset-backed securities market that, including mortgage-backed securities, accounted for 25% of the nearly $40 trillion debt outstanding at the end of 2013.

SEC officials quickly backed down, saying that they would temporarily not enforce the rule so that credit agencies could have six months to adjust. That was four years ago, with no end in sight.

Credit reporting agencies like this state of affairs, because, although they lost the lobbying war to have the expert liability provision deleted from Dodd-Frank, they so far have won the fight to not have to comply with it.

Kathleen Day is a lecturer at The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School(Photo: Handout)

But as the economy recovers, and debt markets rebound, pension funds and other professional investors grow increasingly impatient with inaction by Congress and the SEC. Investors often are required to use credit ratings in weighing the risk a security will default.

Requiring the expert liability standard in SEC filings is one of several provisions in Dodd-Frank intended both to h! old credi! t agencies accountable and, at the same time, reduce the investing public's reliance on their ratings. For example, the act also requires the SEC and other federal agencies to delete references to credit ratings in regulations.

But while Dodd-Frank aims to reduce investors' reliance on ratings, it does not prevent them from doing so. And for those who do, Dodd-Frank says courts can hold a credit agency financially liable if it committed fraud or acted recklessly in preparing a rating. In other words, when credit agencies act irresponsibly, they can no longer rely on First Amendment protection against suits brought by investors.

"If credit rating agencies are deficient or do a bad job, they should be liable for investor losses. The risk of liability is really the only way to get quality control from them," Kelleher says.

Gregory W. Smith, CEO of the Colorado Public Employees' Retirement Association, agrees but is more sympathetic to the political reality the SEC faces. Unlike most other financial regulators, the SEC's budget is part of Congress's annual funding process. That enables financial industry executives who want less oversight to lobby to keep the agency underfunded and therefore constantly short of the manpower needed to do its job of policing markets and implementing new rules and oversight.

"In a perfect world, the SEC would have all the resources necessary to enforce credit rating agency accountability as it was originally contemplated in Dodd-Frank," Smith says.

Spokesmen for S&P and Moody's declined to comment except to say that they should not be held to the same liability standard that auditors face in SEC filings.

Officials at the SEC won't comment except to say that implementing Dodd-Frank is a top priority, which SEC Chairman Mary Jo White reiterated during recent testimony before the House Financial Services Committee. No specific mention of credit rating agency accountability came up at the hearing. Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas)! referred! to a spokesman questions about what, if any, oversight his committee has done on the issue. The spokesman pointed to a 15-month-old statement pledging oversight.

A spokesman for the Senate Banking Committee, chaired by Sen. Tim Johnson (D-S.D.), declined comment.

Kathleen Day is a lecturer at The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School with campuses in Baltimore and Washington. Her e-mail is: kathleen.day@jhu.edu. Website: carey.jhu.edu.

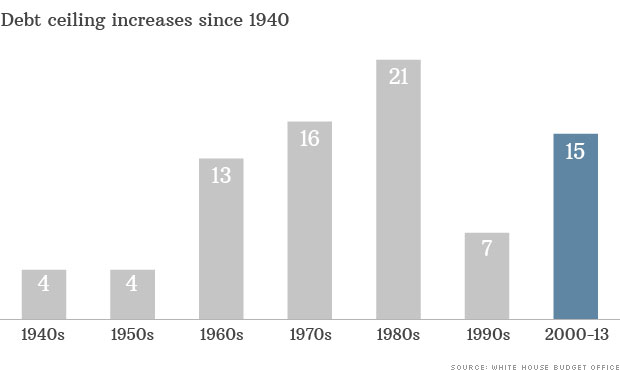

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) Here's how the latest episode of the debt ceiling drama will end: Congress will eventually raise or suspend the country's borrowing limit, probably for as much as a year.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) Here's how the latest episode of the debt ceiling drama will end: Congress will eventually raise or suspend the country's borrowing limit, probably for as much as a year.

181.56 (1y: +28%) $(function() { var seriesOptions = [], yAxisOptions = [], name = 'SPY', display = ''; Highcharts.setOptions({ global: { useUTC: true } }); var d = new Date(); $current_day = d.getDay(); if ($current_day == 5 || $current_day == 0 || $current_day == 6){ day = 4; } else{ day = 7; } seriesOptions[0] = { id : name, animation:false, color: '#4572A7', lineWidth: 1, name : name.toUpperCase() + ' stock price', threshold : null, data : [[1356328800000,142.35],[1356501600000,141.75],[1356588000000,141.56],[1356674400000,140.03],[1356933600000,142.41],[1357106400000,146.06],[1357192800000,145.73],[1357279200000,146.37],[1357538400000,145.97],[1357624800000,145.55],[1357711200000,145.92],[1357797600000,147.08],[1357884000000,147.07],[1358143200000,146.97],[1358229600000,147.07],[1358316000000,147.05],[1358402400000,148],[1358488800000,148.33],[1358834400000,149.13],[1358920800000,149.37],[1359007200000,149.41],[1359093600000,150.25],[1359352800000,150.07],[1359439200000,150.66],[1359525600000,150.07],[1359612000000,149.7],[1359698400000,151.24],[1359957600000,149.53],[1360044000000,151.05],[1360130400000,151.16],[1360216800000,150.96],[1360303200000,151.8],[1360562400000,151.77],[1360648800000,152.02],[1360735200000,152.15],[1360821600000,152.29],[1360908000000,152.11],[1361253600000,153.25],[1361340000000,151.34],[1361426400000,150.42],[1361512800000,151.89],[1361772000000,149],[1361858400000,150.02],[1361944800000,151.91],[1362031200000,151.61],[1362117600000,152.11],[1362376800000,152.92],[1362463200000,154.29],[1362549600000,154.5],[1362636000000,154.78],[1362722400000,155.44],[1362978000000,156.03],[1363064400000,155.68],[1363150800000,155.91],[1363237200000,156.73],[1363323600000,155.83],[1363582800000,154.97],[1363669200000,154.61],[1363755600000,155.69],[1363842000000,154.36],[1363928400000,155.6],[1364187600000,154.95],[1364274000000,156.19],[1364360400000,156.19],[1364446800000,156.67],[1364533200000,156.67],[1364792400000,156.05],[1364878800000,156.82],[1364965200000,155.23],[1365051600000,155.86],[1365138000000,155.16],[1365397200000,156.21],[1365483600000,156.75],[1365570000000,158.67],[1365742800000,158.8],[1366002000000,155.12],[1366088400000,157.41],[1366174800000,155.11],[1366261200000,154.14],[1366347600000,155.48],[1366606800000,156.17],[1366693200000,157.78],[1366779600000,157.88],[1366866000000,158.52],[1366952400000,158.24],[1367211600000,159.3],[1367298000000,159.68],[1367384400000,158.28],[1367470800000,159.75]! ,[1367557200000,161.37],[1367816400000,161.78],[1367902800000,162.6],[1367989200000,163.34],[1368075600000,162.88],[1368162000000,163.41],[1368421200000,163.54],[1368507600000,165.23],[1368594000000,166.12],[1368680400000,165.34],[1368766800000,166.94],[1369026000000,166.93],[1369112400000,167.17],[1369198800000,165.93],[1369285200000,165.45],[1369371600000,165.31],[1369630800000,165.31],[1369717200000,166.3],[1369803600000,165.22],[1369890000000,165.83],[1369976400000,163.45],[1370235600000,164.35],[1370322000000,163.56],[1370408400000,161.27],[1370494800000,162.73],[1370581200000,164.8],[1370840400000,164.8

181.56 (1y: +28%) $(function() { var seriesOptions = [], yAxisOptions = [], name = 'SPY', display = ''; Highcharts.setOptions({ global: { useUTC: true } }); var d = new Date(); $current_day = d.getDay(); if ($current_day == 5 || $current_day == 0 || $current_day == 6){ day = 4; } else{ day = 7; } seriesOptions[0] = { id : name, animation:false, color: '#4572A7', lineWidth: 1, name : name.toUpperCase() + ' stock price', threshold : null, data : [[1356328800000,142.35],[1356501600000,141.75],[1356588000000,141.56],[1356674400000,140.03],[1356933600000,142.41],[1357106400000,146.06],[1357192800000,145.73],[1357279200000,146.37],[1357538400000,145.97],[1357624800000,145.55],[1357711200000,145.92],[1357797600000,147.08],[1357884000000,147.07],[1358143200000,146.97],[1358229600000,147.07],[1358316000000,147.05],[1358402400000,148],[1358488800000,148.33],[1358834400000,149.13],[1358920800000,149.37],[1359007200000,149.41],[1359093600000,150.25],[1359352800000,150.07],[1359439200000,150.66],[1359525600000,150.07],[1359612000000,149.7],[1359698400000,151.24],[1359957600000,149.53],[1360044000000,151.05],[1360130400000,151.16],[1360216800000,150.96],[1360303200000,151.8],[1360562400000,151.77],[1360648800000,152.02],[1360735200000,152.15],[1360821600000,152.29],[1360908000000,152.11],[1361253600000,153.25],[1361340000000,151.34],[1361426400000,150.42],[1361512800000,151.89],[1361772000000,149],[1361858400000,150.02],[1361944800000,151.91],[1362031200000,151.61],[1362117600000,152.11],[1362376800000,152.92],[1362463200000,154.29],[1362549600000,154.5],[1362636000000,154.78],[1362722400000,155.44],[1362978000000,156.03],[1363064400000,155.68],[1363150800000,155.91],[1363237200000,156.73],[1363323600000,155.83],[1363582800000,154.97],[1363669200000,154.61],[1363755600000,155.69],[1363842000000,154.36],[1363928400000,155.6],[1364187600000,154.95],[1364274000000,156.19],[1364360400000,156.19],[1364446800000,156.67],[1364533200000,156.67],[1364792400000,156.05],[1364878800000,156.82],[1364965200000,155.23],[1365051600000,155.86],[1365138000000,155.16],[1365397200000,156.21],[1365483600000,156.75],[1365570000000,158.67],[1365742800000,158.8],[1366002000000,155.12],[1366088400000,157.41],[1366174800000,155.11],[1366261200000,154.14],[1366347600000,155.48],[1366606800000,156.17],[1366693200000,157.78],[1366779600000,157.88],[1366866000000,158.52],[1366952400000,158.24],[1367211600000,159.3],[1367298000000,159.68],[1367384400000,158.28],[1367470800000,159.75]! ,[1367557200000,161.37],[1367816400000,161.78],[1367902800000,162.6],[1367989200000,163.34],[1368075600000,162.88],[1368162000000,163.41],[1368421200000,163.54],[1368507600000,165.23],[1368594000000,166.12],[1368680400000,165.34],[1368766800000,166.94],[1369026000000,166.93],[1369112400000,167.17],[1369198800000,165.93],[1369285200000,165.45],[1369371600000,165.31],[1369630800000,165.31],[1369717200000,166.3],[1369803600000,165.22],[1369890000000,165.83],[1369976400000,163.45],[1370235600000,164.35],[1370322000000,163.56],[1370408400000,161.27],[1370494800000,162.73],[1370581200000,164.8],[1370840400000,164.8

REUTERS

REUTERS

AP

AP